Why I Love Ex-Library Books

Give me your history-laden, your stamped, your dog-eared pages yearning for my shelf

I want to start by telling you a story about one of my favorite books I own. Then, I want to tell you why I love owning ex-library books. By the end, I hope you’ll see the connection.

When I was a student in undergraduate, there was a nearby thrift store which held an entire book room. Not just a book section: a room. I entered college possessed of a steadily growing bibliomania, and at the prices this store sold its books, I could feed that addiction relentlessly. They even offered once-per-month sales where you could buy a box of books for $10. I was hooked.

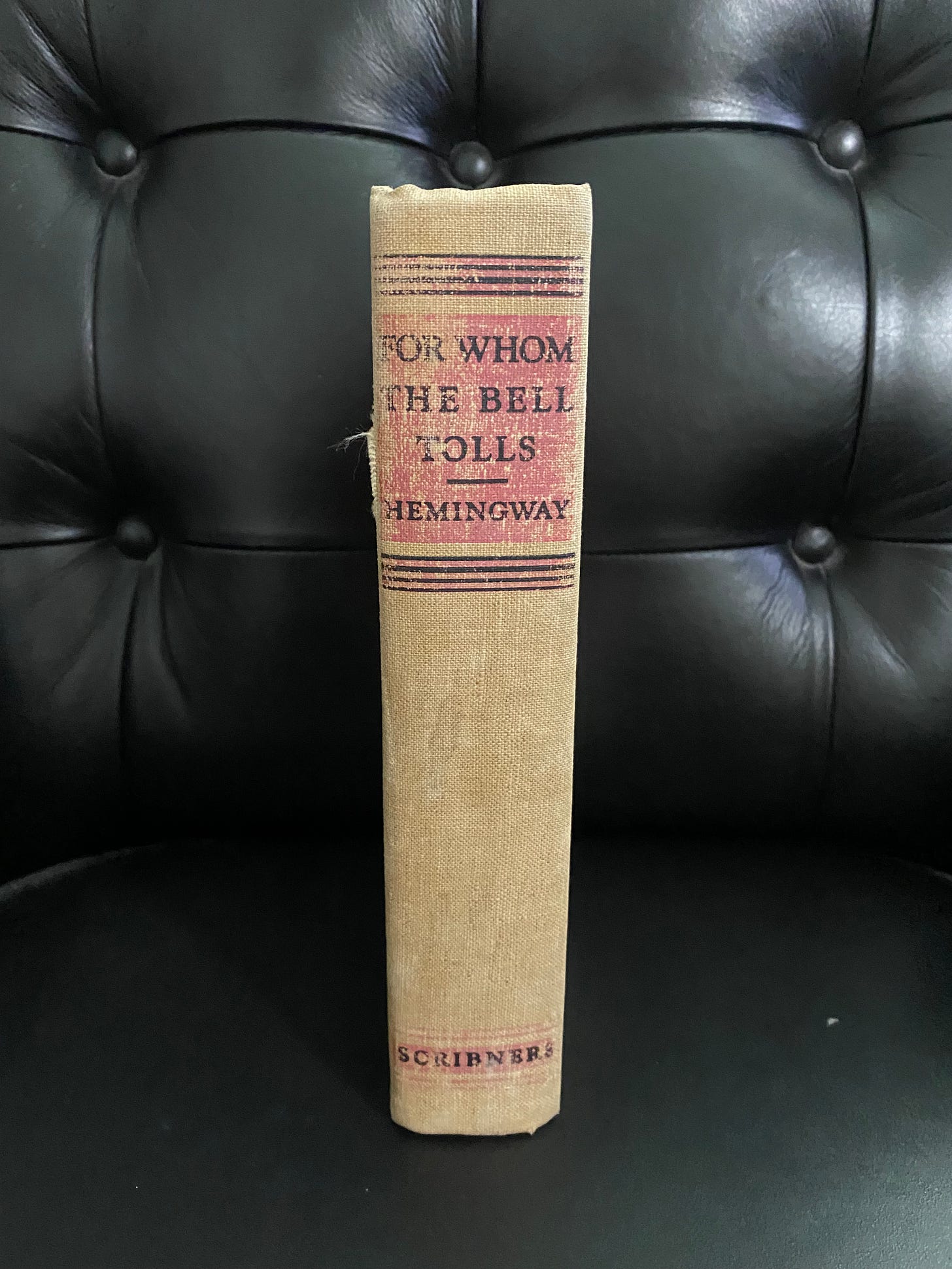

This store had a particular shelf that was labeled “vintage.” The books here were of varying qualities, but one day I happened to spy a very nice looking copy of Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. Having been assigned that particular book for the upcoming semester, I snapped it up with glee and then sort of forgot about it for a time.

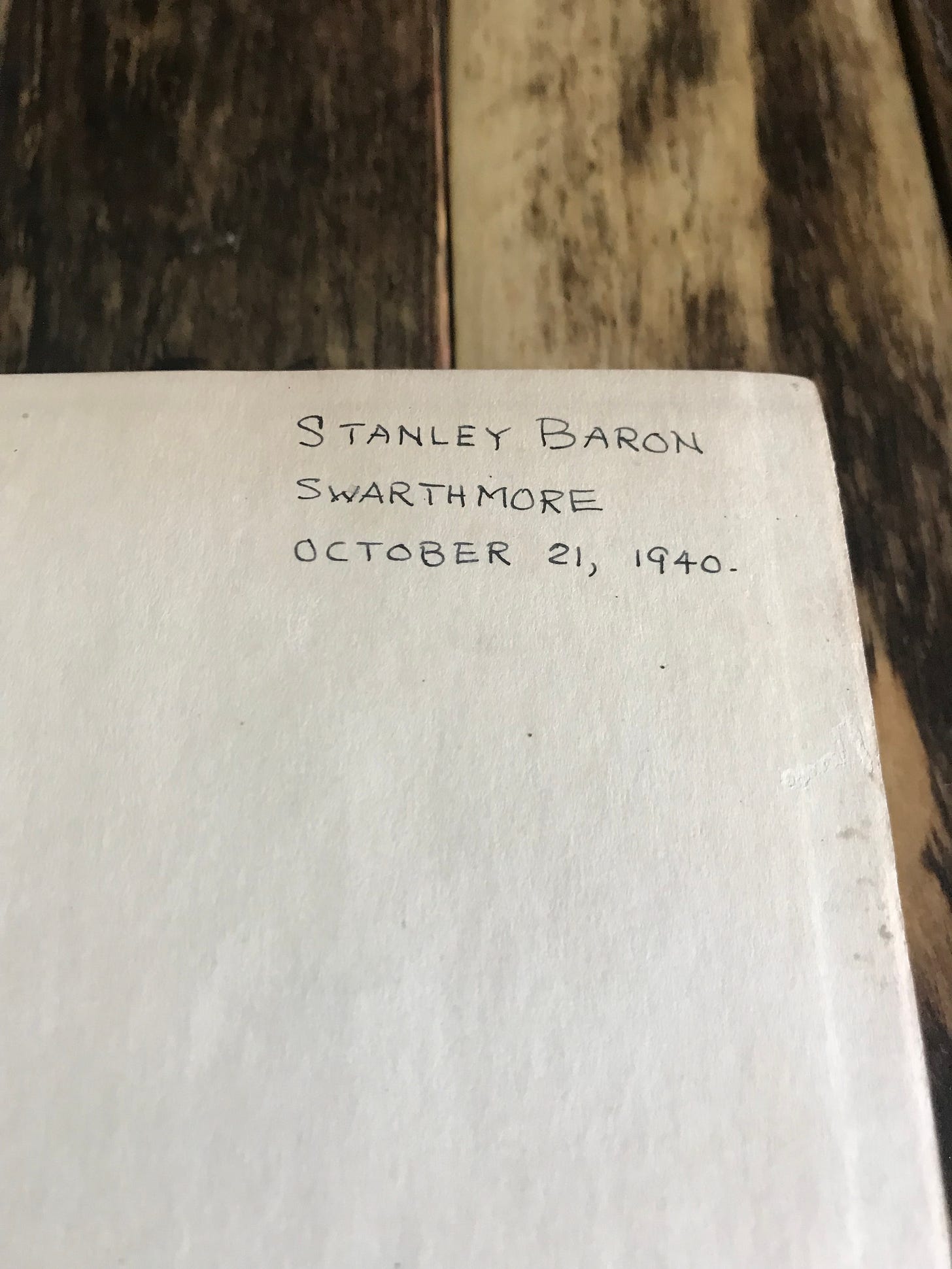

When I picked it up to read later, I discovered two things: First, it was a first edition, first printing of the classic novel. Without its dust jacket and in fairly rough shape, it didn’t hold much monetary value, but as an early book collector, it was a gem: my first major American author first edition! I noticed something else, too: the book was marked on the front. In block letters, someone had carefully written: “Stanley Baron, Swarthmore, October 21, 1940.”

Now, if you don’t have an eidetic memory, you might not know what I later learned, which is that October 21, 1940 was the release date of For Whom the Bell Tolls. Perhaps Mr. Baron just went around marking his books with the date that book was released, but I like to imagine that Mr. Baron of Swarthmore college instead went to the bookstore on the release day of a new work by his favorite novelist and snapped it up posthaste.

Again, I sort of set the book aside for a time and forgot about it, except for the novelty of the date. Later, as I began to be more vigilant in researching the texts I purchased, I went back to Mr. Stanley Baron and decided to determine if he was anyone of note. It turns out that there was one Stanley Wade Baron who graduated from Swarthmore College in 1943. After graduation, he became a figure of minor note, serving as a “political analyst” in the US Embassy in London, but also going on to write a couple of works of detective fiction.

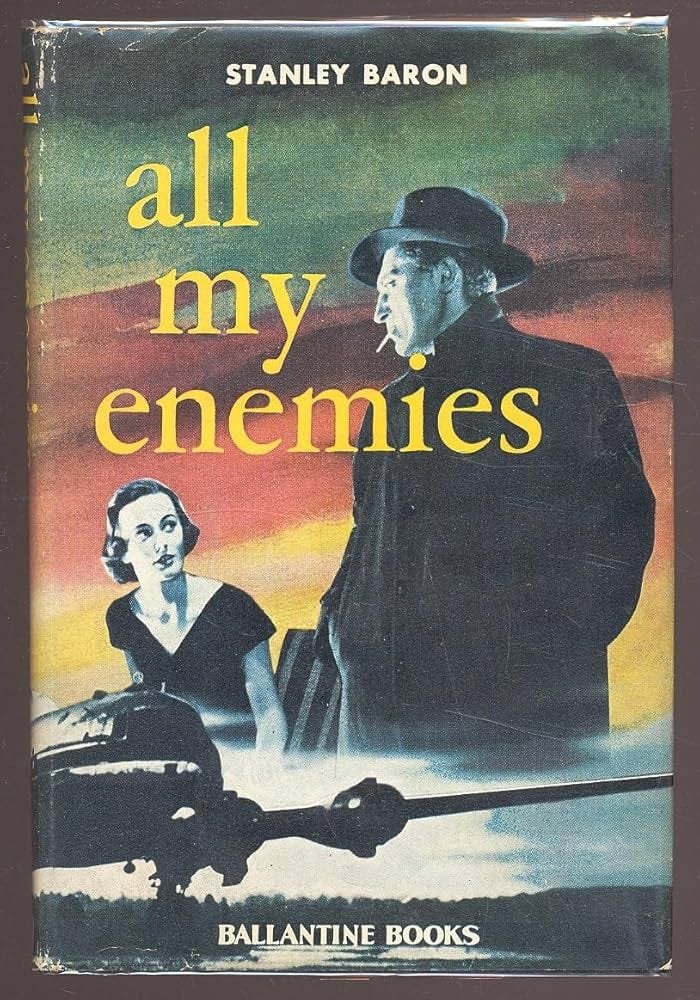

Now, again, if you don’t have an eidetic memory, you might not know that the books Hemingway possessed at the end of his life between his several residences have been meticulously catalogued. Among the books in his library in Cuba on his death? A novel by one “Baron, Stanley Wade. All My Enemies. New York: Ballantine, 1952.”

Who knows if Hemingway read the book or not, but he did in fact own it. I don’t think this story adds any monetary value to the book, but to me it adds immense sentimental, or perhaps “phenomenological” value to the book. A young college sophomore picked up a book by perhaps his favorite author in the year 1940. By 1952, that young man published a work of detective fiction that, whether he knew it or not, would land on the shelves of that same author. What a tremendous record of literary influence.

Now, let’s talk about ex-library books.

Awhile back, I got into something of a tiff on an internet social media platform that shall not be named (it rhymes with Edit). The argument was effectively this: I claimed that I love obtaining ex-library books, and this fellow book collector thought I was full of it.

If you have been book collecting long, you will know that true, serious collectors are often after one particular thing: pristine, first edition, first printing copies with intact dust jackets that look as if they have never heard the whisper of the existence of human hands. Like any other collectable market, a pristine copy of a book, particularly a rare, classic work will command a much higher price than its obviously-used counterpart.

One of the easiest ways for a desirable, collectable book to take a hit in value is for it to be “ex-library.” When books are released, libraries often purchase them immediately. That means, by volume, that a large number of now-rare first edition books, such as those written by 20th century American novelists, first graced the shelves of their local public library or perhaps a university library collection (my former institution has a first edition copy of Cormac McCarthy’s Suttree which I was very tempted to steal, but I remained strong in my principles despite temptation).

But if you have frequented libraries, you will also know that they do things to their books to ensure both their continued possession of them and the longevity of the book itself. So, to prove ownership from those who would steal their property, they often stamp books with ink stamps on the edges and various interior pages. They often also will affix thick plastic covers to their books and then tape or glue these to the boards. In previous eras, they would also use these nifty, now-outdated, “borrowing cards” which would slide into a pocket, again, glued inside the back cover of the book. These things ensure that libraries will usually receive their books back and that the books will have a long life though they pass through many hands.

This also means that the book is irreparably marred from its pristine state, a fact which perturbs many book collectors. Even if one manages to remove a library’s plastic cover, for example, the tape which they used to fix it to the pages will leave permanent scars on the interior and sometimes the cover of the book itself. In some cases, like my first edition copy of Cormac McCarthy’s Child of God, the library will have actually glued the dust jacket to the book boards itself, meaning the jacket is permanently affixed to the book unless you desire to permanently damage both. Because of this, a rare book being labeled “ex-lib” can occasionally cause its value to plummet by a significant percentage, or in some cases even make it next to worthless to a collector.

As I recall the disagreement with my less-than-kind interlocutor, the argument, in effect, was this: if you could afford a pristine copy, of course you would rather have a pristine copy than a damaged one. This means any claim to “prefer” or enjoy ex-library copies is merely a cope designed to make up for your lack of money to obtain the thing you would truly rather have. While I see the point, I think about my book collection quite differently.

The books I come to own are often used, in various conditions. These books have a history all their own. Usually this is a history I cannot track. Many people do not leave their names in books, book plates have fallen out of fashion, and even those who do label their books often fade into obscurity with their passing, making the book’s history opaque at best. But they nevertheless have a history, and this is something I truly cherish about the volumes I own.

In some cases, these histories are more easily traceable and lend the book a meaning that goes beyond its title and contents, such as the story I told you above. Association with an important person is certainly one kind of history I enjoy. True “association copies,” where the book is inscribed to or owned by someone of relevance to the author, are also delightful. But I truly cannot shake a similar delight at learning a book I have just purchased once stocked the shelves of a local library.

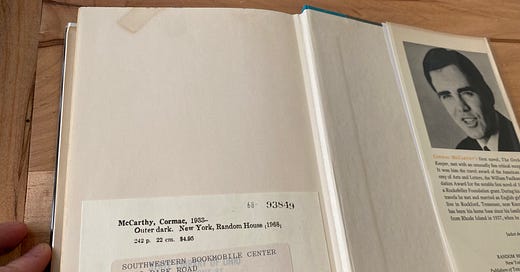

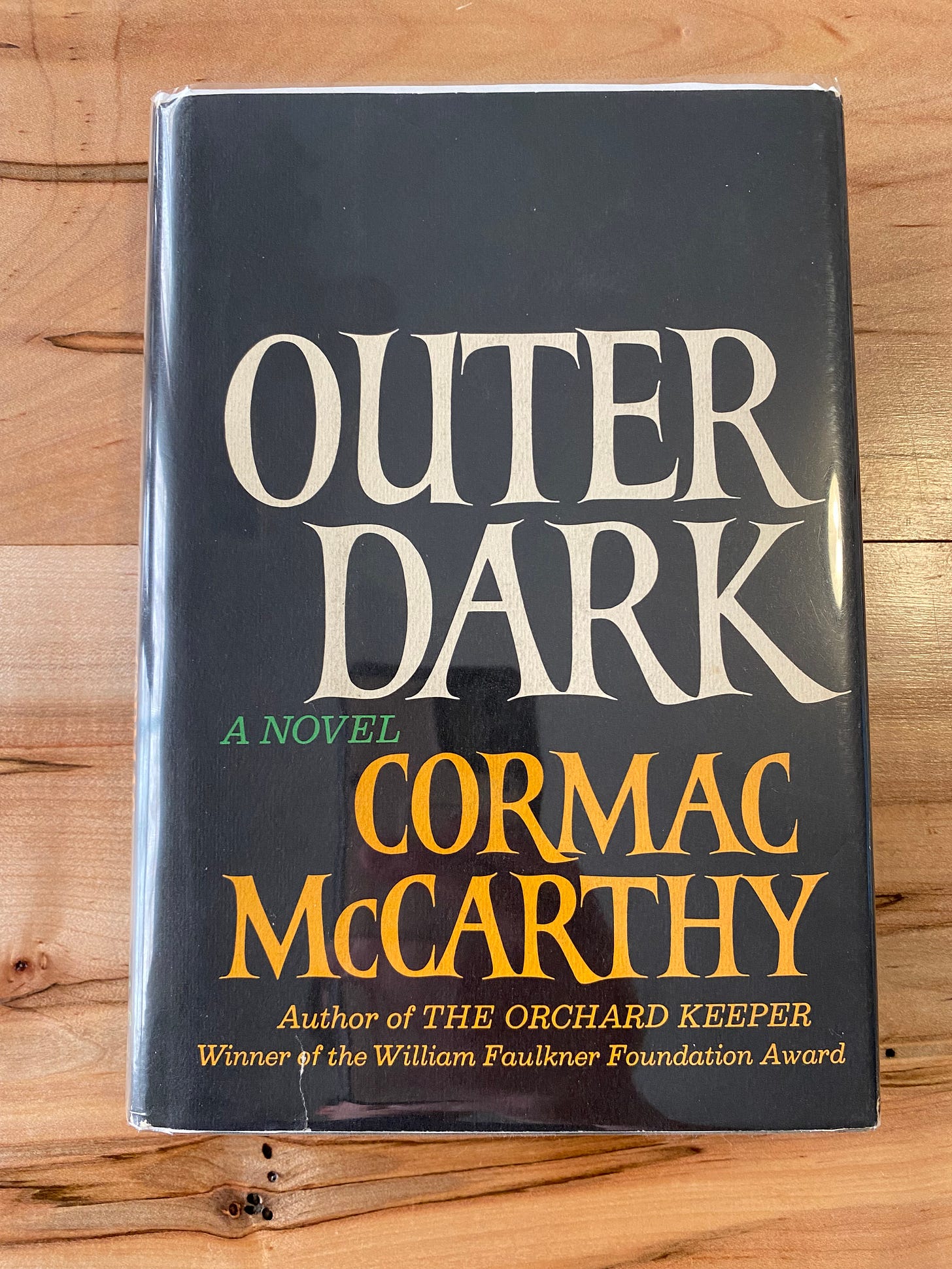

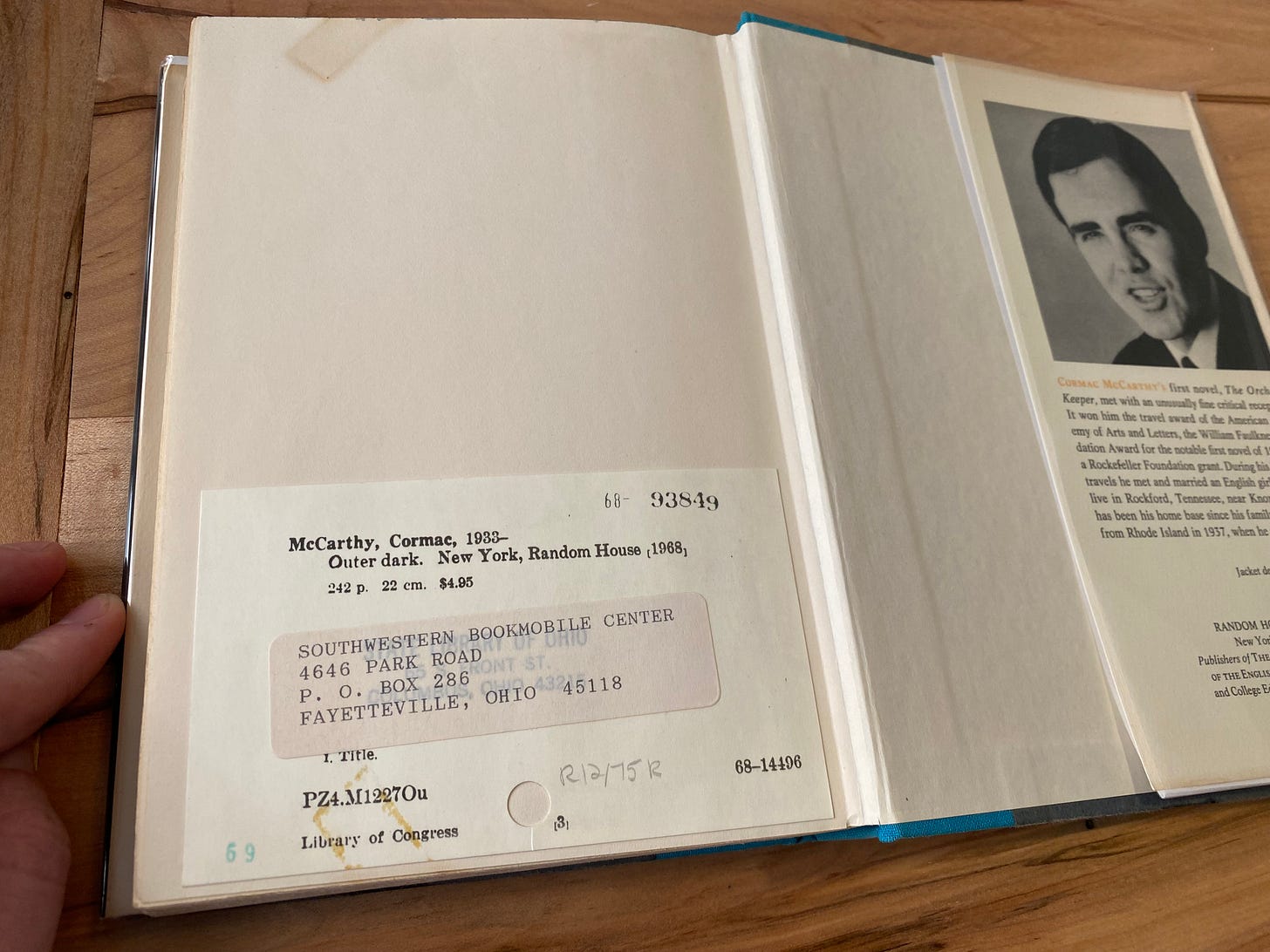

As an example: I own a first edition copy of Cormac McCarthy’s novel Outer Dark. I was able to purchase this because it was auctioned as a damaged, ex-library book. From the outside, you could hardly tell. The book and its dust jacket are in fairly decent shape (nothing a book dealer would call pristine, but good enough for my tastes). But the inside has been marred by tape, handwritten catalogue numbers, and a glued catalogue card at the back that rendered the book undesirable to many collectors, and so I was able to purchase it for a fraction of what this book normally sells for.

But when I open it, smell the pages, and read it, I don’t see the scars, or at least don’t see them as something to be lamented. I see that this book is stamped as having once been in possession of a Bookmobile in a small town in Ohio, perhaps one that wasn’t served by a full public library, so instead was serviced by a van lending books out the back. What a history this book had to go from a public service to that small town to my own personal library. How many people read it? How many of those people were inspired, like Stanley Baron, to go write novels of their own? No pristine copy bears the marks of that history. If those copies are more valuable for their sterility, fine, let the collectors have them. For my part, against my opponent, I do truly value something about these books with rich stories told on their pages. Give me flaws and a story, not sterility and a product.

This is especially true if you’re looking for children’s books, since they often go out of print quickly and if you’re looking to purchase an older children’s book, your only option may be an ex-library copy. As I build a library for my children, I’m always thrilled to stumble upon an ex-library copy of a book I remember checking out as a child - a beautiful continuity between the past and the future.

Wonderful post as usual. This one's close to my heart, because I'm a book designer. I'm surely biased here, but we make books to be read. I spend more hours than I can count (or bill, for that matter) thinking about stuff that the reader never notices unless you get it wrong: things like typeface readability, how much negative space is needed to balance a page's content, whether it's appropriate to break a paragraph to avoid orphan or widow lines. The best reward I get from this work is seeing someone reading a book I helped produce. And I love marginalia, or borrower's cards with many names listed as having checked out the book, or thoughtful dedications telling you this was a gift from a parent or teacher, someone who cared and thought that the reading experience would be appreciated.

Your 'interlocutor' may style themselves as a book collector, but I feel like their values are more closely aligned with speculative asset accumulation. Why else would it matter so much for a book to be in pristine condition? If I could afford a first edition LotR or Narnia, I'd get it, but I wouldn't mind flipping it open to read, or having someone else read it (with reasonable care). Collecting books never to be read, only displayed or resold for profit, strikes me as a bit sad and cynical. Like the guy who buys a Picasso only to keep it in a dark, temp-and-humidity-controlled storeroom. There's probably an argument for that, preservation does matter, but such activity should be for the minority. Don't think it makes the rest of us any less as collectors.