Making Your Own Design for Living

While more lifestyle and entertainment options present themselves to us than ever before, moderns appear paradoxically paralyzed and aimless. People frequently find themselves drifting with no clear direction, no clear place in the world, and no clear vision for the future. This can lead to disillusionment, despair, and loneliness. This trite acknowledgement, or some variety of it, forms the basis of many contemporary commentaries, scholarly and popular, on the human condition in the early part of the 21st century.1

Though this problem can seem particularly acute today, it is quite obviously anything but new. Philosophers, social scientists, and cultural critics have analyzed the trends that have led to the lonely individual since… well, since anyone has been writing about things. As a relatively recent example, Robert Nisbet lamented the loss of traditional community structures in his book The Quest for Community. In his estimation, the “age of individualism and rationalism,” which emphasized such words as “individual, change, progress, reason, and freedom,” had in fact directly led to the more troubling words that fill “modern lexicons.”

These new, frightening words include “disorganization, disintegration, decline, insecurity, breakdown, instability, and the like,” and they dominate our culture’s attempts to understand itself. Paradoxically, our optimism about the potential of humankind, and indeed of each individual, has apparently led to a grim reality. Nisbet writes,

The modern release of the individual from traditional ties of class, religion, and kinship has indeed made him free; but, on the testimony of innumerable works in our age, this freedom is accompanied not by the sense of creative release but by the sense of disenchantment and alienation.

It seems that people, rather than fundamentally desiring to be free and unencumbered by ties that bind, desire a sense of belonging. Though we have sought out and obtained freedom from the ties that previously bound us, we remain unhappy.

Robert Redfield’s “Folk Society”

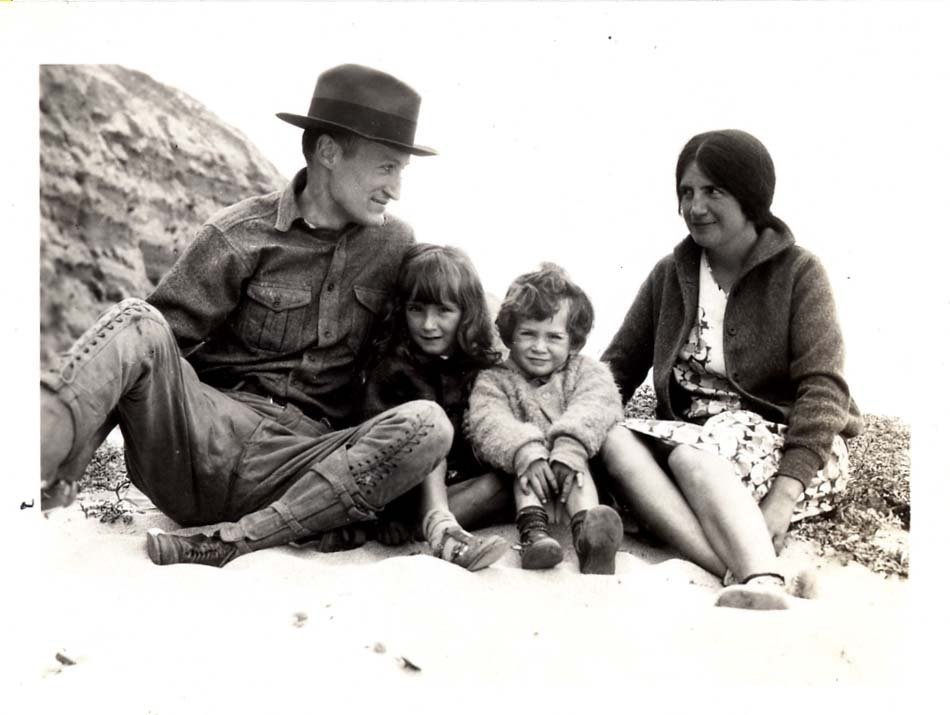

One neglected commentator on this phenomenon that I am doing my best to resuscitate is Robert Redfield. Redfield was co-founder of the University of Chicago Committee on Social Thought, pioneering a multidisciplinary scholarly center with his firm belief in the unity between the social sciences and the humanities. I’ve written elsewhere about his most famous student, Kurt Vonnegut, but I think Redfield is worthy of particular attention, especially as we attempt to address ourselves to the modern malaise so many have identified.

Building on his own field research, Redfield explained this aimless, restless human trend by comparing modern urban and suburban lifestyles with the lifestyle of cultures that seem most foreign to our own. Redfield’s cultural commentary was thus premised on his research on tribal societies in Central and South America, societies that might have been considered more “primitive” than our advanced modern ones, to use relatively outdated terminology. In these tribes, Redfield found elements of what he would come to call the “folk society.”

He described the folk society as one in which life was strongly patterned. Because life in these societies was largely traditional, there was little to no existential questioning, no wondering where you belong. What was expected of you as a member of a tribe, a family, or a faith was clear.

Because of the heavily traditional way of life prevalent in these folk societies, they can be meaningfully said to have a distinct “culture.” Redfield explains,

The ways in which the members of the [folk] society meet the recurrent problems of life are conventionalized ways; they are the results of long intercommunication within the group in the face of these problems; and these conventionalized ways have become interrelated within one another so that they constitute a coherent and self-consistent system. Such a system is what we mean in saying that the folk society is characterized by “a culture.” A culture is an organization or integration of conventional understandings… The folk society exhibits culture to the greatest conceivable degree.

In short, in the folk society, people are given a particular mode of existence. The roles for each member, whether they be a father, a son, a mother, a daughter, a priest, an elder, or whatever else, were clearly defined. This “givenness” inherent in the folk society is clearly contrary to our modern sensibilities that prize self-determination and freedom above any externally imposed, involuntary duties or roles.

In contrast, Redfield referred to the condition of modern man as “designless living.” He presented the case that, while it is possible to live a life with a given design, plan, or structure in which particular people belong, evidenced by the folk society, people in modern liberal democratic societies are provided with no fixed design for living.

In the folk society, man has a sense of unified purpose. In the modern city, there is no such singular sense of purpose. In the folk society, man belongs, both to a community and a family. In the modern city, there is no such guaranteed sense of belonging. Speaking of people who live without a given pattern, Redfield explains, “Their imperatives arise out of nothing deeper than the widespread appetites of human nature and are defined by little more than the popular interests of the moment.”

Redfield describes people who live this way as a “social plankton…They collect briefly in the eddies of fashion and fad, and of the ancient cultures in the deeps below them they know nothing.” While modernity promises the freedom to create your own design, disconnecting from the prescriptions, customs, and wisdom of the past has in fact left us without direction. This is a central critique offered by Nisbet, Redfield, and numerous others before and since.

Practical Remedies?

If our present condition leaves us without a readymade design for living, but we by nature desire to have ordered lives where we have a clear place of belonging, we must seek out what we need or suffer the consequences. What can be done to make your own design for living? Redfield’s cautions and suggestions can be condensed into three practical steps:

First, study the past. If we have gone amiss in our current priorities, we might find ready solutions to our problems in the wisdom of our predecessors. This is Redfield’s primary criticism of those who live aimlessly: they know nothing of the “ancient cultures in the deep below them.” Though we may not be provided with a readymade design for living today, nothing stops us from examining the lives of those who came before us and adopting their values and practices.

Redfield explained, “For my own part I like the old-fashioned virtues; they wear well. There is plenty of good material in what good men have written and lived.” Redfield’s recommendation echoes the writings of Edmund Burke, who suggested that, instead of trading in our “own private stock of reason,” we ought to “avail [ourselves] of the general bank and capital of nations and ages.”

Second, seek to establish some kind of order when you have opportunities to do so. Learning from the past is all but useless if wisdom learned is not put into practice. We ought to use what we learn from the great men and women of the past to create practices and habits that will lead to greater happiness. By studying the past, we can learn what previous generations valued, how they chose to use their time, and consciously take their examples to heart.

We might find, for instance, that we prioritize mindless entertainment over building strong local communities. We might find that we prioritize geographic mobility over putting down particular roots. If our present priorities are disordered, we could examine the priorities of the past an perhaps learn where we have gone awry.

Third, undertake this task with friends and family. Redfield suggests, “It is certainly easier to make the design if the task is shared with those who are most intimate with one. Fortunate is the family whose grown children are its alumni association.” To that end, you should establish habits together with people who share your passions, goals, and values, including your family and closest friends. Circumstances will differ, of course, but if the problem of our age is a rampant, rugged individualism, rectifying the problem can hardly be done alone.

For my own part, I find that my membership in a church and fellowship with other members, friends and family alike, provides much of what Nisbet and Redfield suggest is missing from the modern urban lifestyle. In the traditions and institutions of faith, people find a divine design for living, historical principles of wisdom to guide their conduct, and a place to belong. It is telling that, along with the other institutions of the folk society, moderns have rejected religion or relegated it to a place of relative insignificance; learning from the past would entail learning precisely what we have lost in doing so.

These suggestions are much too broad to be exhaustive. They may not even be terribly useful to many. It is impossible to provide a one-size-fits-all solution to contemporary errors, a foolproof flowchart or algorithmic approach that will give us an easy remedy. As Redfield once explained in a commencement address, “Even if I were wise, I could not tell you in what shape your design should be cut. It is the essence of the situation that it has to be worked out for oneself.”

Conclusion

Redfield was never fully confident that the tragedy of designless living could be “solved” in our current state, but recognized the necessity of trying. He concluded his commencement address on the subject by saying, “I have no sureness that a man may make his own design for living. I only assert that life is worth making the attempt and that without making it, it is worth little.” Redfield, for his part, wagered that we could learn some things about what human beings want and need from the past, both from our actual ancestors in the western tradition and from the cultural predecessors of the modern city found in the “folk society.”

There are, however, things about these so-called “primitive” societies that we would typically consider negatives. For instance, Redfield notes that folk societies are geographically isolated and do not typically engage in communication or trade with neighbors. They also possess few to no written texts and might have no system of writing at all. In short, though we may find significant problems with our present cultural state, we are also the beneficiaries of many practical goods occasioned by our movement away from these cultural norms. Redfield recognized this as well.

This means that one cannot look back on the folk society with reckless nostalgia, hoping to return to a form of idealistic primitivism. Rather, we must take what we learn from societies unencumbered by the trappings of, well, whatever is plaguing us, and see what wisdom about human nature we can glean from them. More than a utopia or a Kallipolis, the folk society as Redfield understood it acts as a foil for us to see our own cultural blind spots more clearly. In so doing, we can perhaps gradually find applicable remedies for our own deficiencies, working together with our friends and family to rediscover the wisdom of the past and put it into practice in whatever modified form suits our time and place. For this, if Redfield doesn’t offer a handbook, he at least offers a starting point for inquiry.

The “terrible disease of loneliness” was a constant theme in the works of Redfield’s student Kurt Vonnegut, particularly in essays contained in his Palm Sunday and Fates Worse Than Death. More recently, Benjamin Storey and Jenna Silber Storey have explored the origins of this phenomenon in Why We Are Restless.